Narcissism is the term used in psychology to describe a preoccupation with self. It is a Greek term taken from the name of the mythological Narcissus, who fell in love with his own image and was doomed to die because he would not turn away from it. A narcissist is a person who displays a high level of selfishness, vanity, and pride. He sees everything from a “how does this affect me?” perspective. Empathy is impossible for the narcissist because his only perspective is the one centered on self. In psychology, narcissism is seen as a broad spectrum of conditions ranging from normal to pathological.

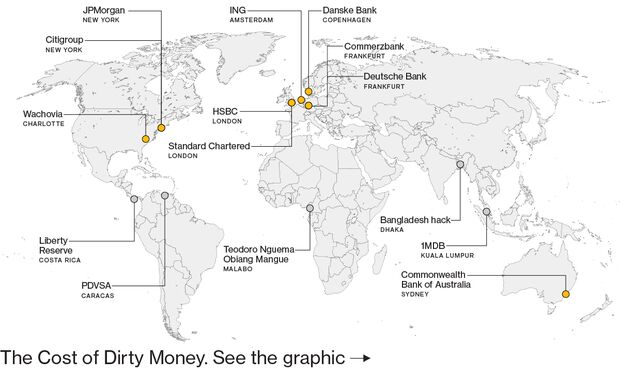

You’re a criminal with millions of dollars in ill-gotten gains but one big problem: Transferring slugs of money or carrying suitcases of cash will raise eyebrows. You need to “launder” the dough — make the dirty money appear to be the proceeds of legitimate enterprise. Then it can be spent anywhere in the world — say, on real estate or luxury yachts — no questions asked. Most countries and all the world’s major banks have controls in place to flag suspicious funds coming into the financial system. But as shown by a series of revelations and the probes roiling European banks, bad actors come up with innovative ways to skirt the rules.

Hiding under shell companies

Deliberately opaque “shell” companies, which exist only on paper and have no active business operations, are easy and cheap to set up and effective at obscuring ownership. They’re key to what experts call the “layering phase” of money laundering, in which funds are shoveled around multiple times to make them harder to track. Shell companies are traditionally foundin offshore tax havens such as Panama and the Bahamas, but the U.S. states of Delaware and Nevada also permit corporations to be set up in anonymity. The international consortium of journalists that uncovered the Troika Laundromat scheme says it involved at least 75 shell companies that generated a total of $8.8 billion in transactions through made-up deals. There’s been a global push for more transparency, even in the U.K., whose crown dependencies include Jersey, Guernsey and the Isle of Man.

Finding weak links

After the chaotic collapse of Soviet Union, launderers searched out weak spots in Europe, where watchdogs were ill-equipped. They looked for banks that might be poorly supervised or even open to being complicit. Torrents of cash were channeled into banks in Cyprus and Malta. Baltic nations Estonia and Latvia, which have central roles in the emerging tale of dirty Russian money, became big players as passageways to the West. The former Soviet states had an added draw because Russian is widely spoken, and Scandinavian lenders rushed to get into the high-growth markets. By way of western correspondent banks, funds could be further cleansed and moved around with less scrutiny. Denmark’s Danske Bank A/S has acknowledged that much of about $230 billion that flowed through its tiny Estonian outpost may have been dirty.

Trade-based money laundering

Criminals can move funds across borders by engaging in seemingly legitimate international trading of goods and falsifying invoices to disguise their true value. Such trade-based laundering was key to the Troika Laundromat scheme, where bogus invoices were allegedly used to trade “food goods,” “metal goods” and “auto parts.” The method is widely used to enable outflows from developing economies. Global Financial Integrity, a Washington-based research organization, estimates that “trade misinvoicing” accounts for 18 percent of developing nations’ trade with developed economies.

Mirror trades

A “mirror trade” is two stock transactions, in two separate locations, that effectively cancel each other out but succeed in moving money from one place to another. Mirror trades have legitimate uses, and are employed by mutual funds and other investors that have limits on where they can hold securities. But such trades can also be used to bring money across borders. In one infamous example, Deutsche Bank AG helped clients move about $10 billion out of Russia from 2011 to 2015 by executing mirror transactions in its offices in Moscow and London. The bank was fined $629 million by U.K. and U.S. authorities for those compliance failures. A criminal investigation by the U.S. Justice Department has yet to conclude. Another technique, sometimes known as a back-to-back deal, is to take a loan in one country that’s secured by a deposit in another country. The launderer defaults on the loan, the bank seizes the deposit and the money looks clean. The fact that both types of transactions have legitimate applications makes them harder to stop.

Mixing clean and dirty money

It’s difficult to tell the difference between legitimate business and illicit flows from criminal activity. Launderers sometimes work with real companies that generate lots of cash, merging their funds before they head to the bank. Casinos and other cash-based operations such as restaurants are attractive targets. A common scheme involving casinos is to buy large amounts of chips in cash, gamble just a tiny share, then call the rest winnings and redeem the funds. Even more effective is owning the whole casino. Macau, the world’s biggest gambling hub, has long been beset by money laundering despite repeated attempts by China’s government to rein it in. Canada found last year that casinos in British Columbia for years served unwittingly as laundromats for domestic and international crime. The expansion of online gaming and sports betting, where identities are easy to conceal, provide new opportunities, as do cryptocurrencies.

‘Smurfing’

To avoid raising red flags, money launderers will break down a large amount of money into smaller chunks and have associates known as “smurfs” deposit the funds in different accounts in different places. U.S. banks are required to report to regulatory authorities any transaction of more than $10,000, so launderers often avoid hitting that limit. Banks must continuously track customer transactions to look for red flags, and if they have good reason to suspect something devious, they must alert authorities. Failure to do so can bring stiff fines. Banks often complain that the rules are onerous and the controls needed to “know your customer” are costly. Danske Bank increased the number of employees in compliance after its money-laundering scandal exploded, and now has more than 1,000 people assigned to monitor and prevent financial crime. Source

HSBC PLC HSBA, +1.15% yesterday reported a rise in profits to $17.2 billion but it was short of analysts expectations and shares fell over 3% following its earnings announcement.

But there are some who feel HSBC can still count itself fortunate for not being more heavily punished over their failure to prevent Mexican and Colombian drug cartels from laundering hundreds of millions of dollars through the U.S. financial system.

HSBC, Europe’s biggest bank, paid a $1.9 billion fine in 2012 to avoid prosecution for allowing at least $881 million in proceeds from the sale of illegal drugs. In addition to facilitating money laundering by drug cartels, evidence was found of HSBC moving money for Saudi banks tied to terrorist groups. Even though federal investigators found evidence “that senior bank officials were complicit in the illegal activity,” no HSBC executives faced charges for their actions. The Wall Street Journal revealed in 2016 that U.S. Justice Department officials, led by President Obama’s former Attorney General Eric Holder, overruled their prosecutors’ recommendation to pursue criminal charges against HSBC in 2012.

Last December, the deferred prosecution agreement (DPA) that HSBC had entered into with the Department of Justice officially expired, providing confirmation that the U.K. bank, which generates the lion’s share of its revenue in Asia, would pay no further penalty for its money-laundering controls.

However, the spotlight has turned back onto HSBC’s money-laundering lapses by “Cartel Bank,” an episode of Netflix’s new corporate-malfeasance documentary series “Dirty Money” specifically devoted to the scandal.

Netflix has not disclosed ratings for “Dirty Money,” which was released January 26, but analysts estimate it is among the most highly rated documentaries in the streaming giant’s history and the series has a 100% rating on Rotten Tomatoes.

Kristi Jacobson, who directed the “Cartel Bank” episode, said she has been pleasantly surprised at the positive reaction to the documentary from inside the financial community. Rejecting claims that HSBC was sufficiently penalized with the $1.9 billion fine it received in 2012, Jacobson said: “The fine they received was equivalent to approximately five weeks of their yearly profit.”

“Since the series has come out, I have talked to a number of people in the financial world who have said to me, ‘This is your best work’ largely because they too were outraged at the lack of legitimate and real accountability. So I’ve found that it has crossed partisan lines and gone all the way into the financial world,” Jacobson said.

Jacobson’s previous documentary subjects include supermax facility Red Onion State Prison in Virginia (“Solitary”) and starvation (“A Place at the Table”). “Financial corruption isn’t something I’ve previously covered in my work and when I started to learn the details of this case, I was shocked by the corporate malfeasance and the multiple times they were caught breaking the law,” she said.

“I was driven to make documentaries by my understanding of social justice issues and what I view as the brokenness of our criminal justice system. This was a unique and different way to show that brokenness as well as the way that government can work and should work, but doesn’t work,” she said.

In revealing the full extent of the ties between HSBC and Mexico’s Sinaloa Cartel, “Cartel Bank” features contributions from HSBC whistleblower Everett Stern, former U.S. Attorney William Ihlenfeld and Anabel Hernández, a Mexican investigative journalist.View image on Twitter

Well, I won’t bank with HSBC now

#DirtyMoney#HSBCBloodMoney711:28 AM – Feb 18, 2018See G.Man’s other TweetsTwitter Ads info and privacy

Jacobson added: “It wasn’t just HSBC’s money laundering crimes over many years for the most notorious drug cartels. It was their admission of it and then their audacity to continue to commit those crimes.”

“I felt it was important to make the connection between that conduct and the actual human toll, the deaths of more than 100,000 people in Mexico as a result of drug-related violence and the disruption in the U.S. relating to drugs coming across the border and enabling international criminal organizations to operate,” she said.

Jacobson was hired by the project’s executive producer Alex Gibney, the acclaimed Oscar-winning documentary film director. “It’s an appalling story because those bankers were too big to jail,” said Gibney. “We hear a lot about the war on drugs but when you have a bank like HSBC that is literally making drug-dealing possible through money laundering, you wonder why is it they can’t be held to account.”

Jacobson said she couldn’t help but contrast the actions of HSBC with the incarcerated subjects of her Virginia prison documentary “Solidarity” that aired on HBO a year ago. “These are two different sides of the same problem,” she said.

“That experience reflected what I think is the American way — to overpunish in terms of sentences for poor people, people of color, people who are powerless. HSBC was underpunished. A kid busted for marijuana possession can’t get away with saying, ‘I haven’t done a good job and I’ll change my behavior,’ as HSBC was allowed to.”

HSBC did not cooperate with Jacobson on her documentary. When asked for comment, a spokesperson for HSBC said: “In 2012 we apologized unreservedly for the historical weaknesses in our financial crime controls as part of the announcement of the deferred prosecution agreement with the Justice Department.”

“Since then, we have done an enormous amount of work to improve our financial crime controls and procedures, something that the Justice Department acknowledged when releasing us from the DPA on schedule in December.”

“We’re also going to keep investing in risk and compliance so that our controls become even more effective, and our clear aim is to be the industry leader in the fight against financial crime.”

Jacobson said: “We sought HSBC’s participation and they declined. Since the film has been out, I haven’t had any direct contact with them, partly because the facts revealed in the film are documented in the DPA (the Deferred Prosecution Agreement) that HSBC co-wrote and signed, making it as unimpeachable as one can get telling this kind of story.”

“But on the day the trailer came out, they dropped a note to our associate producer noting that the charges had been dropped and that it was important for us to tell that story. That was the last time we heard from them,” she said.

In response to the scandal, HSBC has significantly strengthened its compliance programs and appointed an external corporate monitor.

Despite the heavy financial penalty for HSBC following the scandal, eleven banks have incurred higher fines than them during the last decade. MarketWatch recently revealed that banks have been fined a total of $243 billion since the financial crisis with HSBC paying out $4.5 billion. Source

Share

PrintSAN DIEGO —

Dutch lender Rabobank’s California unit agreed Wednesday to pay $369 million to settle allegations that it lied to regulators investigating allegations of laundering money from Mexican drug sales and organized crime through branches in small towns on the Mexico border.

The subsidiary, Rabobank National Association, said it doesn’t dispute that it accepted at least $369 million in illegal proceeds from drug trafficking and other activity from 2009 to 2012. It pleaded guilty to one count of conspiracy to defraud the United States for participating in a cover-up when regulators began asking questions in 2013.

The penalty is one of the largest U.S. settlements involving the laundering of Mexican drug money, though it’s still only a fraction of the $1.9 billion that Britain’s HSBC agreed to pay in 2012. It surpasses the $160 million that Wachovia Bank agreed to pay in 2010.

Three execs behind cover-up

Under the agreement, the company will cooperate with investigators. The federal government agreed not to seek additional criminal charges against the company or recommend special oversight.

The settlement describes how three unnamed executives ignored a whistleblower’s warnings and orchestrated the cover-up. Two of the executives were fired in 2015 and one retired that year.

“Settling these matters is important for the bank’s mission here in California,” said Mark Borrecco, the subsidiary’s chief executive.

In 2010, Mexico proposed new limits on cash deposits at the country’s banks, resulting in more tainted deposits at Rabobank branches in Calexico and Tecate, according to the plea agreement. Accounts in the two border towns soared more than 20 percent after Mexico’s crackdown, and bank officials knew the money was likely tied to drug trafficking and organized crime.

Risky customers escaped scrutiny, including one in Calexico who funneled more than $100 million in suspicious transactions. Customers in Tecate withdrew more than $1 million in cash a year from 2009 to 2012, often in amounts just under federal reporting requirements.

“The cartels probably thought these were sleepy towns, no one’s going to notice,” said Dave Shaw, head of U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement’s Homeland Security Investigations in San Diego. “When you bring in $400 million, someone is going to notice. The bank should have known and they just chose not to report any suspicious activity.”

Punishment for cover-up, not crime

Heather Lowe, legal counsel and government affairs director at research and advocacy group Global Financial Integrity, said the illegal activity bore similarities to what happened with HSBC and Wachovia.

But those banks were charged with laundering Mexican drug proceeds, while Rabobank only acknowledged covering it up.

“It seems in this case we have the bank taking the hit for lying but not for the violations themselves,” said Lowe, who expects the three unnamed executives will be prosecuted.

A whistleblower alerted two of the three executives to suspicious activity in 2012 and shared her concerns with the bank’s “executive management group,” according to the plea agreement. She also spoke with regulators amid concerns in the company that the government scrutiny could endanger a pending merger. She was fired in July 2013.

The government has a cooperating witness in former compliance officer George M. Martin, who agreed in December to cooperate with authorities in a deal that delayed prosecution for two years.

Martin, a vice president and anti-money laundering investigations manager, acknowledged he oversaw policies and practices that blocked or stymied probes into suspicious transactions and said he acted at the direction of supervisors, or at least with their knowledge.

Martin told investigators that he and others allowed millions of dollars to pass through the bank.

Rabobank, based in Utrecht, Netherlands, said last month that it set aside about 310 million euros ($384 million) to settled allegations against its subsidiary. Sentencing is scheduled May 18.

#Money #steal #BadBanks #Bad Bankers #Fraud #crushpeople

The Bible says that we are born sinful since the fall (Romans 5:12). This means that we are born with only sinful tendencies and no ability to be “good” or righteous on our own. What we call “human nature” the Bible calls “the flesh” (Galatians 5:19-21). Part of our sin nature is a total focus on self. This focus, also called “egocentrism,” is how babies see and experience the world. Narcissism is like egocentrism in that the adult still relates to the world like an infant, a perspective that impedes personal growth and relationships.

Psychological theories about narcissism suggest that the narcissistic person uses defense mechanisms to idealize self so that he does not have to face his own mistakes (sin) or flaws (fallen state). The diagnosis of narcissistic personality disorder outlines the behavior patterns of a narcissistic person as being haughty, non-empathetic, manipulative, and envious; he also possesses a sense of entitlement and grandiosity. From a biblical perspective, it is clear that these heart conditions are due to pride, which is sin (Proverbs 16:18). The Bible tells us to “look not only to your own interests, but also to the interests of others” (Philippians 2:4). The narcissist routinely disobeys this command.

Pride is a reason people do not feel they need a savior or forgiveness. Pride tells them they are “good” people or have a “good” heart. Pride also blinds people to their own personal responsibility and accountability for sin. Narcissism (pride) masks sin, whereas the gospel reveals the truth that leads to remorse for sin. Narcissistic traits can be dangerous because, at their worst, they will lead a person to destroy others to satisfy the lust of the flesh (2 Timothy 3:2-8).

The Bible addresses the issues related to narcissism as part of our sinful natural self (Romans 7:5). We are slaves to the flesh until we place our faith in Jesus, who sets the captives free (Romans 7:14-25; John 8:34-36). Believers are then slaves to righteousness as the Holy Spirit begins the transforming work of sanctification in their lives. However, believers must surrender to the Lord and humble themselves in order to have God’s perspective rather than a selfish one (Mark 8:34). The process of sanctification is turning away from self (narcissism) and turning toward Jesus.

All people are narcissists until they either learn how to cover it and get along in the world or until they recognize their own flesh and repent of their sin. The Lord helps people to grow out of narcissism when they receive Jesus as their savior (Romans 3:19-26). The believer is empowered to begin loving others as himself (Mark 12:31).

StevieRay Hansen

Editor, Bankster Crime

MY MISSION IS NOT TO CONVINCE YOU, ONLY TO INFORM…

Fraud #Banks #Money #Corruption #Bankers

“Have I therefore become your enemy by telling you the truth?”

#chilssextrade #pedophiles #lawlessness #mexican #children #molested #kill #badbusiness

![]()

Banks Are In Trouble: Wells Tumbles As Revenues Plunge, NIM Hits Record Low, Warns On Payment Deferrals

If there is one constant during earnings season, it is that no matter what the other banks do, Wells Fargo will always shit the bed,…

Read More