Megabanks Like the Big Four in the United States Produce Financial Instability and More Severe Crises, Big Bank Collapse Coming

BanksterCrime:

By Pam Martens and Russ Martens:

It took eight years of research to compile a data set of annual balance sheets of more than 11,000 commercial banks dating back to 1870 in 17 advanced economies. And in every country, the study arrived at the same finding: concentrating the banking system in the hands of five or less giant banks leads to financial instability and more severe financial crises. The bank balance sheets of the following countries were examined: Australia, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, and the United States.

The 150-year banking study is titled: “Survival of the Biggest: Large Banks and Financial Crises.” Its authors are Matthew Baron of Cornell University; Moritz Schularick of the Kiel Institute for the World Economy and Sciences; and Kaspar Zimmermann of the Leibniz Institute for Financial Research SAFE.

Other key findings from the study include the following:

“First, we find that large banks are substantially less likely to fail in banking crises than smaller banks. Smaller banks also tend to be absorbed at high rates by large banks in the aftermath of crises. As a consequence, the market share of large banks tends to grow in crises, making them even more dominant going forward. We call this repeated pattern during crises the ‘survival of the biggest.’ We show that the aftermath of banking crises can account for 40% of the total increase in top-5 banks’ asset share across history.”

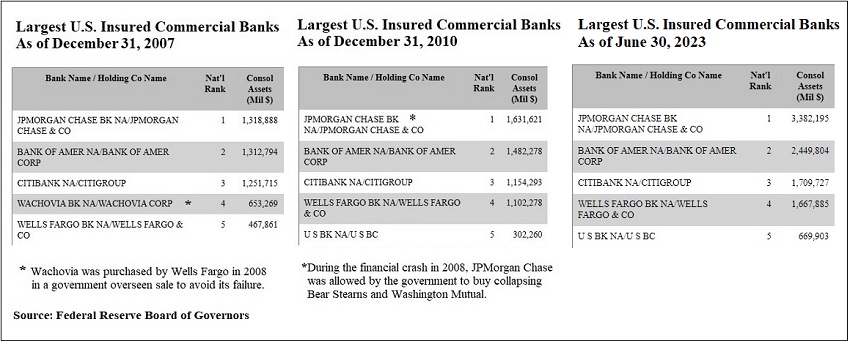

Let’s pause here for a moment and examine that finding in relation to what happened during the financial crisis of 2008 in the United States and this past spring. The largest bank holding company by assets in 2008 was JPMorgan Chase. During the 2008 crisis, federal regulators allowed JPMorgan Chase to buy Bear Stearns and Washington Mutual as they collapsed. JPMorgan Chase went on to admit to an unprecedented five felony counts brought by the U.S. Department of Justice between 2014 and 2020 and developed a rap sheet rivaling an organized crime family; but that didn’t stop its federal regulators from handing it First Republic Bank and its approximately $200 billion in assets after First Republic failed this past spring. As our chart below shows, JPMorgan Chase has more than doubled in size since 2010 to $3.38 trillion in assets as of June 30. Bank of America has grown by almost $1 trillion in assets since 2010. Wells Fargo has grown by $1.2 trillion since the financial crisis.

Despite mega banks in the U.S. creating the worst financial collapse since the Great Depression in 2008, federal regulators handed the same problem banks more assets during the 2008 financial crises. (Bank of America was allowed to buy Merrill Lynch during the financial crisis in 2008 and Wells Fargo was allowed to buy Wachovia Bank during the crisis.)

Another key finding from the new study also buttresses the findings of the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission following the financial collapse of 2008 in the U.S. The authors write:

“One may ask whether ‘survival of the biggest’ is due to more prudent behavior of the large banks in the run-up to crises. Our second finding is that the opposite is true. Large banks typically take more, not less, risk than smaller banks in the run-up to crises, and large banks suffer bigger equity losses and contract their lending more in the aftermath of crises.”

So why would federal regulators allow these imprudent banking behemoths to grow even larger during a crisis? The authors write:

“…We show two (potentially interconnected) results: first, policymakers are substantially more likely to rescue top-5 banks on the verge of failure, and, second, large banks have more stable funding dynamics in crises, despite greater equity losses. To show the first of these results, we systematically examine top-20 banks across all historical banking crises and create a database of government rescues at the individual bank level—specifically, for all banks that exit or have stock returns less than -90% (which we interpret as being ‘on the verge of failure’). We find that, among banks ‘on the verge of failure,’ interventions explicitly intended to prevent failure and preserve the original banking institution are very common for top-5 banks but a lot less common for banks 6-20 (which instead tend to be merged away or wound down).”

In the U.S. since 2008, the Federal Reserve Bank of New York has become the perpetual money spigot to the reckless banking behemoths. Despite having no elected officials, the New York Fed is allowed to create money electronically out of thin air to shore up the mega banks’ balance sheets when their reckless trading activities require mending.

The study’s authors do not venture into the dangerous political waters seeking an explanation as to why governments continually rescue reckless big banks but in the U.S. two words tend to sum up the problem: regulatory capture. As these banks become giants, they also gain political heft and a rapidly spinning revolving door. For example, Citigroup’s Citibank was clearly insolvent during the financial crash of 2008. Between January 1, 2008 and March 30, 2009, Citigroup’s stock had lost more than 90 percent of its market value. But instead of winding it down, the Federal Reserve Bank of New York secretly infused over $2.5 trillion in revolving loans into Citigroup’s sinking hulk between December 2007 and July 2010 according to an eventual audit by the Government Accountability Office.

The authors also take on the perceived wisdom that mega banks add to stability in the banking system. They write:

“…One of the primary concerns is that large banks might be perceived as ‘too-big-to-fail’ by regulators and creditors, allowing these banks to take excessive risks. Additionally, their size and complexity as organizations can make them more difficult to regulate or harder to implement effective risk management and corporate governance. Their greater number of interconnections with other financial institutions adds to risk and amplifies contagion effects. And they may have greater access to risk-taking opportunities, such as access to risky trading activities and to greater international opportunities for risk taking, than small banks. Some prior research shows that larger banks tend to take more risk than smaller banks (Boyd and Runkle, 1993; Boyd and Gertler, 1994; Gropp et al., 2011; Huber, 2021). Laeven, Ratnovski and Tong (2016) study large global banks around the 2007-08 financial crisis and find that the largest banks around this crisis have higher leverage, less deposit funding, are organizationally more complex, and create more systemic risk. We similarly find that risk taking during credit booms in the run up to systemic banking crises is higher for large banks across history.”

And, finally, the authors dispel the quackery from the legions of publicists and lobbyists that work for the banking giants who are paid to say these mega banks make the banking system safer. The authors write:

“…finally, history shows that, contrary to widely held beliefs, banking systems dominated by a few large banks are not measurably safer than more fragmented banking systems. The frequency of banking crises is not lower in large-bank-dominated banking systems. In fact, conditional on experiencing a crisis, real economic outcomes are more severe in banking systems dominated by a few big banks.”

Serious attention is being paid to this study. The paper was presented at the FDIC’s 22nd Annual Bank Research Conference on September 28; at the Sixteenth New York Fed/NYU Stern Conference on Financial Intermediation on May 5; and a presentation was scheduled for last Friday at the Wharton Conference on Liquidity and Financial Fragility. In addition, in a footnote in the paper, the authors thank “seminar and conference participants at Bonn, Chicago Booth, Cornell, the ECB, IESE, Leibniz Institute for Financial Research SAFE, the OCC, the OFR, Universitat Pompeu Fabra, USC, the AFA annual meeting, Bundesbank financial intermediation conference, EFA annual meeting….”

The mention of the OCC and OFR in the above list would suggest that shockwaves might be occurring in Washington. The OCC is the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, the federal bank regulator that was criticized severely by Senator Elizabeth Warren at a July hearing for allowing JPMorgan Chase to purchase First Republic Bank and get even larger and more dangerous. (See JPMorgan Chase, Officially the Riskiest Bank in the U.S., Is Allowed by Federal Regulators to Buy First Republic Bank.)

The OFR is the Office of Financial Research, which was created under the Dodd-Frank financial reform legislation of 2010 to function as an early warning system for financial regulators to alert them when systemic risks were building in the U.S. banking system. The OFR has repeatedly warned that the concentration of risks in a handful of mega banks poses a financial stability problem. Its warnings have fallen on deaf ears among captured members of Congress and captured regulators.

According to a 2015 OFR research paper:

“The larger the bank, the greater the potential spillover if it defaults; the higher its leverage, the more prone it is to default under stress; and the greater its connectivity index, the greater is the share of the default that cascades onto the banking system. The product of these three factors provides an overall measure of the contagion risk that the bank poses for the financial system. Five of the U.S. banks had particularly high contagion index values — Citigroup, JPMorgan, Morgan Stanley, Bank of America, and Goldman Sachs.”

All five of these banks played a key role in the financial crisis of 2008.

The same OFR report also made the following finding:

“A bank that has large foreign assets and large intrafinancial system liabilities is a potential source of spillover risk. If a large loss in value in foreign assets caused such an institution to fail, the losses could be transmitted to the rest of the U.S. financial system. Five banks had large foreign assets (exceeding $300 billion) and Citigroup and JPMorgan had large figures for both foreign assets and intrafinancial system liabilities.”

Since the OFR wrote those words in 2015, the situation has gotten exponentially worse at Citigroup and JPMorgan. (See our report from last week: After Getting the Largest Bailout in U.S. History in 2008, 85.5 Percent of the $1.34 Trillion in Deposits at Citigroup’s Citibank Lack FDIC Insurance Today.)

The authors of this critically-needed study, together with law professor, Arthur Wilmarth, who wrote the seminal work on the history of how the U.S. ended up with today’s dangerous banking system, Taming the Megabanks: Why We Need a New Glass-Steagall Act, can provide Congress with the roadmap to get us out of this mess.

The authors of this critically-needed study, together with law professor, Arthur Wilmarth, who wrote the seminal work on the history of how the U.S. ended up with today’s dangerous banking system, Taming the Megabanks: Why We Need a New Glass-Steagall Act, can provide Congress with the roadmap to get us out of this mess.

We call on the Senate Banking Committee and the House Financial Services Committee to immediately schedule hearings with these critically-important researchers.

Revelation: A Blueprint for the Great Tribulation

A Watchman Is Awakened

Will Putin Fulfill Biblical Prophecy and Attack Israel?

Newsletter

Orphans

Editor's Bio