BanksterCrime:

by Tyler Durden

Submitted by Nic Carter

- New bankruptcy filings and exclusive interviews with confidential sources suggest Silvergate could have survived if not for pressure from regulators, which allegedly included an informal mandate to cap its crypto deposits at 15 percent

- Sen. Elizabeth Warren all but accused Silvergate of aiding and abetting FTX’s crimes, creating an “atmosphere of concern” around Silvergate that possibly contributed to a run on the bank

- Sources told us the FHLB (Federal Home Loan Banks) refused to renew their monthly loan agreement with Silvergate due to political pressure from Warren, accelerating the bank’s losses

- Claims of criminal wrongdoing related to Silvergate’s association with FTX have never been proven, and no criminal charges have ever been filed against the bank

- Silvergate’s downfall may have been a primary cause of the 2023 regional banking crisis, which ultimately took down Signature, Silicon Valley Bank, and First Republic

In late 2022, Silvergate Bank was on top of the crypto world. Once a small California savings and loan association, Silvergate had transformed itself into the most important bank in the crypto sector, allowing it to stage an IPO and claim a majority of the sector’s institutional deposits. The bank’s Silvergate Exchange Network (SEN) had grown to become a crucial piece of infrastructure for crypto’s institutional players, and shares in the company had surged from $35 at the end of 2020, to $220 at the end of 2021.

Today, Silvergate no longer exists. Although its depositors were made whole, common shareholders were completely wiped out, and preferred shareholders are getting back pennies on the dollar. The bank paid out large fines to its regulators: $43 million to the Federal Reserve, $20 million to California’s Department of Financial Protection, and $50 million¹ to the Securities and Exchange Commission. After having announced their intent to voluntarily liquidate in March 2023, they finally filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy last week.

Those who still remember Silvergate see the bank as emblematic of crypto’s worst elements and the most reckless behavior exhibited by regional banks during the crisis of 2023. A perfect storm of risk-seeking, turning a blind eye to crypto criminals, and compliance failures. Or at least — that’s how the story goes.

This story — today presented as established fact in the financial press and by the government² — goes like this:

Silvergate was a sleepy, small regional bank until it discovered crypto. When the space experienced surges of interest in 2017 and again in 2020, balance sheet expansion caused Silvergate’s deposits to swell. The bank then turbocharged its usefulness to the crypto space when it created SEN, allowing its clients — which now included many of the world’s largest crypto exchanges and trading firms — to settle between each other 24/7/365. (Because crypto settles 24/7, and bank wires only clear during banking hours, firms linking fiat and crypto often experience serious friction. SEN helped alleviate these issues.) Most crypto firms that mattered were clients of Silvergate, lending SEN powerful network effects.

In 2017, Silvergate onboarded Alameda Research, a secretive trading firm run by Jane Street alum Sam Bankman-Fried. Alameda quickly grew to become one of the most active trading shops in crypto, deepening its dependence on Silvergate. When Bankman-Fried launched FTX, a flashy offshore exchange in the vein of Bitmex or Binance, Silvergate started processing wires for them, too.

Silvergate grew to occupy a critical position in the domestic crypto industry. In the two years following Q4 2019, deposits ballooned from $1.8 billion to $14.3 billion. By year-end 2021, digital asset customers at Silvergate maintained $11.7 billion on deposit with the bank, equivalent to 82 percent of total deposits.

Not long after, things began to go south in crypto. In May, the ponzi-esque “stablecoin” UST, issued by Do Kwon’s Terra, went belly up. Then, over the summer and fall, lenders Voyager, Celsius, and BlockFi blew up in quick succession as a credit crunch hit the industry. In June, “proprietary” trading firm Three Arrows Capital collapsed due to its remarkably stupid long bets on Terra/Luna, causing further reverberations as the firm absconded with investor cash. The coup de grâce came in November 2022, with the messy and extremely public collapse of Sam Bankman-Fried’s empire in the Bahamas.

Throughout this period, balance sheets at crypto banks shrank as firms tried their best to satisfy their obligations and pay down their debt — or went out of business. Consequently, Silvergate suffered dramatic outflows, with non interest-bearing deposits (a large portion of which were attributed to crypto firms) falling from a peak of $14 billion in December 2021 to $7.4 billion in December 2022.

Silvergate faced significant problems on both the asset and liability sides. The liabilities were deposits owed to crypto firms in the process of shrinking their balance sheets or outright failing. The assets were treasury bonds, agency securities, and municipal bonds cratering in value due to dramatic federal interest rate hikes aimed at stemming advanced inflation. As the bank’s crypto depositors withdrew, Silvergate was forced to sell its newly depreciated long-dated bonds for a fraction of their original value, resulting in a net loss in calendar year 2022 of $948 million.

Simultaneously, questions began to emerge about Silvergate’s role in the FTX fiasco. Was it just a bank with a settlement network, or something more sinister? When Sam Bankman-Fried was processing funds in and out of FTX via Alameda, had Silvergate deliberately looked the other way? Had Silvergate been aware of the holes in Alameda’s and FTX’s balance sheets? Had the bank been party to the litany of ancillary crimes committed by SBF et al., which included campaign finance violations and bribing Chinese officials? As one of the most important banks for the Alameda/FTX apparatus, it was certainly plausible Silvergate was a co-conspirator.

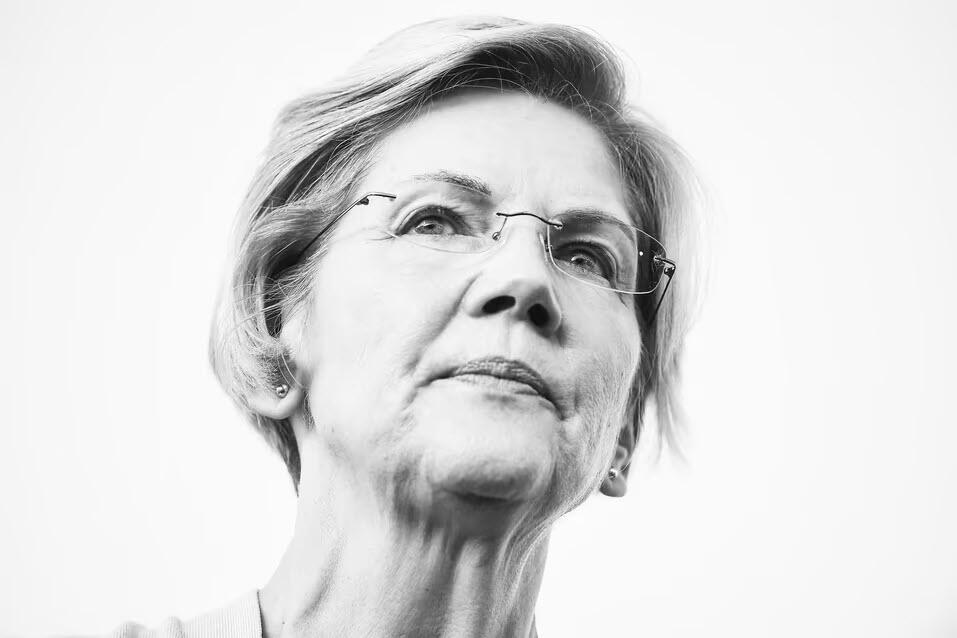

These were the questions posed by an unlikely confederation of short sellers and high-level members of Congress. First, the bombastic short seller Marc Cohodes implied Silvergate was not only doomed, but actually implicated in SBF’s crime syndicate. Then, Cohodes’ claims found surprising support from one of the most important political voices in finance: Massachusetts Senator and member of the Senate Banking Committee, Elizabeth Warren. Warren wrote two letters to Silvergate CEO Alan Lane in December 2022 and January 2023, lambasting the bank and lending credence to claims that it might have criminal liability stemming from its relationship with FTX.

Reacting to these concerns, the Federal Reserve, FDIC (Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation), and OCC (Office of the Comptroller of Currency) issued a joint statement warning banks they faced significant risks if they served the crypto space. Two days later, Silvergate slashed costs and downsized to adapt to their shrinking depositor base. Another joint statement from federal bank regulators, again on the risk crypto posed to banks, soon followed. Meanwhile, shares in Silvergate were collapsing, falling to $16 by the end of 2022.

For the plucky Silvergate, this all proved too much to bear. On March 8, 2023, Silvergate leadership announced its intention to voluntarily liquidate the bank. This was an unusual move — normally failed or failing banks are sent into receivership (placed under the control of a government-appointed entity, typically the FDIC), then sold off to larger, sounder banks. But given the risks of criminal liability from the FTX fiasco hanging over the bank, perhaps it made sense to just shut it down completely.

To the average pundit, there’s nothing wrong with this story. Silvergate bet big on a risky industry and faced the consequences when a credit crunch led to a depository flight. It had onboarded the odious Sam Bankman-Fried, and possibly become party to his crimes. Meanwhile, the bank had greedily backed its short term liabilities (customer deposits) with long term, higher yielding instruments, and were forced to realize huge losses as they honored withdrawals. As a relatively small bank, Silvergate didn’t have the capital buffer to absorb these losses, so it chose to wind down.

The warnings from Senator Elizabeth Warren had proved prescient. By 2024, Silvergate had settled with the Fed, California’s financial regulator, and the SEC, with individual executives paying fines and being barred from the business. This was all the confirmation anyone needed that Silvergate had lied about its compliance program and had experienced significant surveillance failures in their engagement with FTX/Alameda. Silvergate took on inadvisable risks by serving the generally fraudulent crypto space, got greedy by betting on long-duration, higher-yielding bonds, and paid the ultimate price.

But what if that’s not the whole story?

What if there’s another version of events, in which Silvergate was a victim of FTX, not an accomplice to their crimes?

What if Senator Warren’s warnings about Silvergate served as a self-fulfilling prophecy, hastening the run on the bank?

What if the Biden administration deliberately killed off Silvergate — and some of its peers — in an attempt to decapitate the domestic crypto industry? What if this was the spark that lit the flame of a gigantic regional banking crisis?

And what if the settlements Silvergate made with its regulators effectively covered the government’s tracks, allowing it to continue to deny the existence of Operation Choke Point 2.0?

This is the version of events no one is talking about, and one that official government accounts rebuke, but it’s what I’ve come to believe. Aside from a relative few on Crypto Twitter, it’s a story no one seems interested in — the mainstream financial press most of all. But in my mind, the official narrative is historical fiction at best, and recent events have only further convinced me of the fact.

Until now, Silvergate executives have been muzzled by regulatory actions and litigation, unable to tell their side of the story. Based on conversations with confidential sources, and new revelations in Silvergate’s recently public bankruptcy filings, I believe Silvergate could have survived its drawdown — and was on a path to do so — before being hamstrung by regulators continuing to advance the covert Biden admin scheme to destroy the US crypto industry we now know as Operation Choke Point 2.0. In so doing, government officials eliminated Silvergate’s ability to operate as a bank focused on the crypto industry, and forced their “voluntary” liquidation.

I further believe the targeted harassment of Silvergate which led to its downfall was a primary cause of the 2023 banking crisis, which ultimately took down Signature, Silicon Valley Bank, and First Republic, and threw the broader banking system into disarray.

In short: the government’s desire to decapitate the domestic crypto industry through covert rulemaking aimed at crypto-focused banks both initiated and worsened the banking crisis of 2023, the largest since the great financial crisis in 2008.

I first started hearing from individuals at Silvergate, Signature, Silicon Valley Bank, and First Republic that they were under inordinate pressure from regulators in early 2023. At the same time, multiple regulatory agencies were firing warning shots across the bow of crypto-adjacent banks. There was Elizabeth Warren’s hostile letter to Silvergate, the January 2023 joint statement from three regulatory bodies regarding crypto risk to banks, the Fed’s denial of crypto-focused Custodia’s application to become a Federal Reserve member bank, and the National Economic Council (NEC) cautionary statement on banks and crypto.

In response, several banks that provided services to crypto firms began to curtail or eliminate their digital lines of business entirely. This retreat was reminiscent of Operation Choke Point, an Obama-era program aimed at marginalizing politically disfavored industries like firearm manufacturers not by passing legislation, but by using financial regulators to threaten banks providing services to those industries. In my first piece of reporting for Pirate Wires on the topic, I coined “Operation Choke Point 2.0” to describe how these same tactics were being used against the crypto space. At the time, Silvergate was under significant pressure, but still operational.

Thirty days after I published Choke Point 2.0, Silvergate would announce its voluntary liquidation. The following day, Silicon Valley Bank’s collapse began in earnest, and on Sunday night, New York regulators sent Signature Bank following into receivership, despite protests from board member Barney Frank that the bank was still solvent, and that the move was politically motivated.

Based on discussions with individuals with knowledge of the affected banks, I wrote a follow-up piece for Pirate Wires, alleging that Silvergate had been forced to close due to a secretly imposed 15 percent cap on crypto deposits, and that Signature had been wrongly put out of business. Additional provocations included the FDIC’s unwillingness to allow Signature to sell off its crypto-focused deposits or its SigNet product, a 24/7 settlement layer similar to Silvergate’s SEN. Instead of maximizing value for taxpayers by securing a price for the assets, the FDIC instead allowed these crypto-related lines of business to wither on the vine. Signature’s crypto deposits were forcibly returned to clients rather than being inherited by its acquirer, Flagstar Bank. By threatening the banks themselves, these actions not only looked like a covert attack on the crypto space, but they also potentially hastened, or even caused the demise of, the two most pro-crypto banks in the US.

The Silvergate story was particularly vexing because, unlike at Signature, no one was able to speak out and tell their side of the story. I later learned that key elements of the regulatory crackdown, in particular the 15 percent threshold on crypto deposits (conveyed to Silvergate by the SF Fed, with apparent assent from other regulatory bodies) were considered “confidential supervisory information” (CSI)³, and hence ineligible to be shared publicly. Perversely, CSI is intended to protect banks themselves from leaks of information surfaced in examinations — routine procedures where regulators evaluate bank management, safety and soundness, and regulatory compliance — that could hurt their standing, but in this case, it was weaponized against the banks to protect the regulators’ reputation in the eyes of the public.

So far, we have seen no acknowledgment from the Fed, its regional branches, or the FDIC regarding the 15 percent deposit caps, which government authorities primarily messaged verbally to a number of crypto banks, rather than in writing. Why did Silvergate and others feel compelled to comply with these informal deposit caps? An insider explained it to me this way: “They have eight million ways to shut us down, any way they want. When they say you gotta do something, you do it.” The caps were never publicly discussed or formally opposed as a rule, but when your primary regulator threatens you, you comply. “The regulators can pick anything and say, ‘Your compliance program is broken’ as a pretext for shutting you down,” the source told me.

According to people briefed on the situation, though the 15 percent threshold on crypto deposits was issued to Silvergate by the SF Fed, it originated in DC. It is now widely suspected that the architect of this policy was Bharat Ramamurti, then-deputy chair of Biden’s National Economic Council, a powerful advisory body that coordinates economic policy across many executive agencies. Ramamurti was senior counsel for banking and economic policy in Senator Elizabeth Warren’s office from 2013 to 2019 and economic policy director on her 2020 campaign. Now, he’s an advisor to the Harris/ Walz presidential campaign.

When I reported on Choke Point 2.0, there was little on the record to corroborate my findings, as Silvergate leadership and other insiders were ensnared in regulatory settlements and litigation, prohibiting them from speaking publicly. But Silvergate’s recent bankruptcy filings allowed them to tell their side of the story for the first time.

The first-day bankruptcy filing from Silvergate Chief Administrative Officer Elaine Hetrick lays out the company’s side of the story, to the extent legally permissible. She starts by noting the difficulties Silvergate faced due to the crypto market downturn and the significant interest rate hikes, but maintains the bank had sufficient assets to operate as a going concern in early 2023. The bank’s challenges, however, “reached an inflection point in early 2023 following further regulatory scrutiny regarding its business model.”

Hetrick states that in early 2023, Silvergate “had stabilized, was able to meet regulatory capital requirements, and had the capability to continue to serve its customers,” but maintains that “the increased supervisory pressure on Silvergate Bank and other banks focused on servicing crypto-asset businesses forced Silvergate Bank to a point where it would have needed to remake its business model away from its focus on crypto-asset businesses.”

After the phrase “the increased supervisory pressure on Silvergate Bank,” Hetrick adds a footnote: “Silvergate is prohibited by law from disclosing confidential supervisory information, which broadly includes correspondence and communications with the Federal Banking Regulatory Agencies as well as reports of supervisory examination.” This means there’s more to be said about the nature of the pressure — which in my view would include the verbally-messaged 15 percent cap on crypto deposits — but Hetrick is prohibited from going into detail here, due to the supervisory pressure being considered CSI.

Hetrick is adamant that sudden regulatory shifts, not the financial difficulties it had faced from the drawdown in deposits, forced Silvergate to shutter. In initial filings, she explains: “This public signaling and sudden regulatory shift made clear that, at least as of the first quarter of 2023, the Federal Bank Regulatory Agencies would not tolerate banks with significant concentrations of digital asset customers, ultimately preventing Silvergate Bank from continuing its digital asset focused business model.”

She also points to the failure of Signature Bank as indicative of an anti-crypto stance on the part of regulators, referring to Chair Barney Frank’s comments that its closure was at least partially due to a desire to “send an anti-crypto message.” Hetrick notes that, tellingly, the FDIC refused to include $4 billion in crypto-related deposits in the sale of Signature to Flagstar Bank. As one confidential source told me regarding the FDIC’s refusal to sell crypto-related deposits or Signature’s SigNet, “The government is setting policy not based on law, but through selective sales.⁴”

For now, Hetrick is unable to share the full extent of regulatory pressure the Fed applied to Silvergate, but her testimony, given under oath, is still extremely revealing. Notably, it’s a stark departure from the official government account as written by the GAO (Government Accountability Office), which makes no mention whatsoever of the novel regulatory pressures that ultimately doomed the bank.

One of the first clues something with Silvergate’s downfall was suspicious was that it chose to voluntarily liquidate in March 2023, rather than entering FDIC receivership. This is so uncommon that I had to dig deep to find similar examples, and even then, I could only identify a tiny handful in the last 30 years. The most notable was West Virginia’s First National Bank of Keystone, a small bank with $1.1 billion in assets which voluntary liquidated in 1999 before eventually being taken over by the FDIC. Aside from First National, I couldn’t find any voluntary liquidations of banks with over $100 million in assets. It’s truly a rare thing. In fact, a source told me that when Silvergate leadership expressed its intention to voluntarily liquidate the bank, their California regulator, having no experience with the procedure, was completely unsure of how to proceed.

Why is this notable? In my view, how rarely banks choose voluntary liquidation is further evidence Silvergate was ultimately killed by regulatory mandate, not the bank run it suffered. After all, in March 2023 — when the bank voluntarily liquidated — it had already survived the run. In fact, deposits had ticked up quarter over quarter from Q3 to Q4 2022.

Instead, I learned the economics of the business simply didn’t make sense after regulators imposed the new 15 percent crypto deposit limit. SEN would be rendered useless, as the bank wouldn’t be able to maintain accounts with all the relevant firms that would be transacting. And the drastically reduced revenue streams would no longer justify the high fixed costs of supporting crypto firms (especially from a compliance perspective). Sources told me leadership even considered charging large clients high fixed fees for banking access — believing they would be willing to pay, since so few other banks served crypto at that time — but they couldn’t make the numbers work. So they chose to wind the bank down in an orderly manner and make all depositors whole, which they were able to do.

We don’t know what would have happened had Silvergate been given the opportunity to rebuild its business after it right-sized following the bank run, rather than being permanently hamstrung by the 15 percent crypto deposit cap. We do know that the balance sheets of crypto firms recovered strongly in the US in 2023 and 2024, as the credit crunch ended and large caps like Bitcoin rallied once again.

“If the [15 percent] limit hadn’t been imposed, Silvergate would be thriving right now,” someone familiar with the matter told me. I tend to believe this. There has been a gaping hole in domestic crypto banking since the imposition of Choke Point 2.0, and any firm brave enough to offer banking to crypto firms would have done tremendously well — had any been allowed to survive. Anecdotally, connections to domestic banks willing to onboard crypto clients is the number one request from portfolio companies at my blockchain-focused venture capital firm Castle Island. Unfortunately, regulators haven’t allowed the market for crypto-friendly banks to recover. As a result, crypto startups are moving offshore, where more banks are willing to support digital asset firms.

On the first day of 2023, there were three major banks commonly known to serve crypto firms: Silvergate, a smallish bank almost exclusively focused on crypto; Signature, a relatively large bank with a significant but not exclusive concentration of deposits from crypto firms; and Metropolitan Commercial Bank, another boutique with a crypto arm. Silicon Valley Bank also had a single large crypto client in stablecoin network Circle. Four months later, they were all gone, reminiscent of the Henry VIII nursery rhyme about his doomed wives — “divorced, beheaded, died.” In this case, it was “liquidated/ collapsed/ acquired, exited the crypto business, and collapsed/ acquired.” At the two most notable crypto boutiques — Silvergate and Signature — there is strong evidence they were actively destroyed by regulators, rather than dying of natural causes.

Any bank looking to fill the hole left by these three institutions would have faced a frigid regulatory environment and the presumed informal 15 percent cap on crypto deposits that rendered the economics infeasible. Previously, a bank could orient itself toward the crypto space and justify the investment in a tech stack and compliance overhead if they could expand their depository base, as Silvergate and Signature did. They could also create valuable intra-bank settlement networks like SEN and SigNet if they were able to get a meaningful share of the crypto industry under one roof.

With hundreds of crypto firms in the US suddenly without banking access after Signature et al. went down, many chose to move over to fintech firms like Mercury, but things were still extremely tenuous. Even today, few banks are willing to onboard crypto firms, especially if they need more bespoke services beyond simple cash management. Those that serve the crypto industry do so quietly, cognizant of the fact that if they become known as a “crypto bank,” they’ll be maimed by regulators.

This is exactly what happened to the two banks that tried to fill Silvergate’s and Signature’s shoes. After they ceased operations, Customers and Cross River were the two firms known to still bank crypto firms. And both were punished by their regulators.

In May 2023, the FDIC hit Cross River with a consent order, which kneecapped the bank’s crypto efforts. Although the order didn’t mention Cross River’s crypto business, and it covered the bank’s fintech partnerships, it’s still plausible that it came on the FDICs radar due to its prominence as one of the few remaining pro-crypto banks.

More directly, in August 2024, the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia issued an enforcement action against Customers Bank, citing deficiencies with the bank’s “risk management practices and compliance with the applicable laws, rules, and regulations relating to anti-money laundering” in connection with its digital assets business. Just like Silvergate’s SEN and Signature’s SigNet, Customers operated an instant settlement business for clients called Customers Bank Instant Token (CBIT).

Such intra-bank settlement networks appear to be utterly toxic to regulators. Sources with knowledge of the Cross River and Customers matters to whom I spoke surmised that the Fed’s July 2023 release of FedNow — an instant payment service that allows banks and credit unions to settle transactions in real time, 24/7 — could explain the Fed’s particular hostility toward banks that had created their own instant settlement networks. Certainly many view the timing as suspicious. I’m not entirely persuaded by the theory, but the fact that SEN, SigNet, and CBIT were all eliminated or defanged around the time FedNow launched did raise eyebrows.

Since the imposition of Choke Point 2.0 in early 2023, other banks have tentatively sought to fill the gap left by Silvergate and Signature, and later by Customers after it curtailed its crypto efforts. It’s become a running joke at this point — I periodically hear about certain banks launching a crypto practice, then invariably, months later, they will abruptly reverse course. I can personally attest that this has been the case at MVB Bank and Axos Bank, but there are undoubtedly more.

These days, if a bank does serve crypto clients, it keeps the service to a deliberately small portion of its depository base, and tends to downplay it in public. As a result, crypto startups find it difficult to even identify banks willing to serve them, and the few banks who still support institutional crypto clients are slow-moving, expensive, and unwilling to offer services beyond mere cash management.

As an aside, it’s worth noting that in 2023 and 2024, the FDIC extended its Choke Point 2.0 playbook from banks serving crypto to banks serving non-crypto fintech startups as well. In April 2024, the American Fintech Council (AFC) wrote a letter to the FDIC accusing it of using its enforcement powers to quietly curb fintech activity in the US by bringing selective enforcement against banks serving fintech firms. As the AFC said in their letter: “While your agency has not issued public guidance or other statements explicitly admonishing or limiting banks from engaging in partnerships with fintech companies we have identified a distinct ‘regulation by enforcement’ approach from the FDIC.” The AFC noted that banks not partnered with fintechs had a 1.8 percent chance of facing an enforcement action from the FDIC, whereas fintech-partnered banks had a 15 percent chance of a regulatory rebuke.

Just as with Choke Point 2.0 efforts against crypto, the government’s mode of engagement with fintech has been unusually antagonistic and ideological in nature. Instead of proposing new legislation and hosting a public debate, or even engaging in notice-and-comment rulemaking where affected parties would have the right to provide feedback, these agencies make arbitrary new rules and impose them by enforcement — and whispered “advice” which banks have no choice but to follow.

Critics reading this article could point out that Silvergate did end up facing a consent order from the California Department of Financial Protection and Innovation (CA DFPI), which carried a $20 million fine. They also paid a $43 million fine to the Federal Reserve, and settled with the SEC for $50 million (though the bank was able to ‘apply’ the $63 million it had already paid to the latter, so they never actually paid the SEC anything). It’s worth noting that Silvergate has well over $100 million remaining on the balance sheet and has already paid out the $63 million in fines, so these fines would not have put them out of business had they still been operational.

So what if regulatory pressure doomed Silvergate? They clearly made mistakes, and so the short sellers and Senator Warren were right… right? If you dig into the settlements, the actual charges against the bank fall short of the critics’ worst claims — and none are criminal. (In February 2023, the Justice Department initiated a fraud probe to investigate the bank’s dealings with Alameda/ FTX, but nothing has since materialized.)

As for the SEC and California Fed settlements, Silvergate neither admitted nor denied any of the allegations made.

The SEC case against Silvergate hinges on the fact that the bank and its CEO Alan Lane made “misleading statements to the investing public that the bank’s BSA [Bank Secrecy Act]/ AML [Anti-Money Laundering] compliance program was adequate,” a far cry from the most hysterical charges levied by Warren and the bevy of critics. As one source briefed on the situation explained to me, the core of the SEC’s allegation was that Silvergate’s regulatory examinations showed “matters requiring attention” in their BSA program, so it was misleading to represent to the public that they had a “robust AML program.” However, virtually every bank examination includes some nominal “matters requiring attention,” as there are always areas for improvement.

Regarding Silvergate’s failure to detect FTX’s various schemes, banks are not expected to catch every single instance of suspicious activity among their clients, although leaders at the bank did tell me they regretted not detecting FTX’s sketchy behavior. The SEC did initially attempt to claim that Silvergate was aiding and abetting the fraud at FTX, but they were unable to prove anything to that effect.

“Where we were not as buttoned up as we should have been was in regards to the FTX/Alameda clients. That was a function of the bank growing incredibly quickly,” a Silvergate executive told me. “Probably we could have figured out FTX was brokering deposits via Alameda. In retrospect I think we could have pieced this together and figured it out. But this is not a legal failure and we’re not required to catch everything. Our program passed legal muster. That’s something we could have done a better job of. But there was no intentional wrongdoing or cooperation with the bad guys.”

In the FTX investigation, Silvergate was listed as a victim, not a co-conspirator.

Of the three settlements, executives at Silvergate felt the SEC’s case was the least warranted. “The SEC was crazy. They wanted headlines. They were hitting us unnecessarily,” one told me. As I mentioned above, the SEC’s case didn’t concern Silvergate’s compliance failures, but instead perceived falsehoods in what their leadership said about its BSA/ AML program. According to a Silvergate executive that I spoke with for this story, “The SEC was stretching mild conclusions from the Fed and exaggerating them.” One wonders why the SEC would invest energy in suing a defunct bank that did not lose money for depositors — especially if the agency didn’t actually collect any fines for the trouble.

The Federal Reserve settlement hinges on “deficiencies in Silvergate’s monitoring of internal transactions through the SEN.” As one source described it: “When you read the language, it’s pretty milquetoast” — the settlement contains no allegations of affirmative wrongdoing. The actual issue, I discovered, was that Silvergate’s transaction monitoring system for SEN had gone through an upgrade and experienced an outage. Because SEN was a settlement network for Silvergate’s own clients, every transaction on SEN was between clients known to the bank that had gone through rigorous KYC (Know Your Customer) and onboarding processes. So even during the monitoring outage, it’s not like the transactions were between unknown firms. One source told me that SEN volumes were around $2 trillion in the aggregate; massive transfers were common, so FTX/Alameda transfers would not necessarily have stood out as suspicious.

Why would three regulators sue a bank that had already agreed to voluntarily liquidate, and ensured that depositors were made whole? The fines came out of investors’ pockets, mainly hurting common shareholders — ordinary members of the public. Deterrence, perhaps. But there’s a darker interpretation: regulators wanted to publicly establish unlawfulness to stand in for the real reason Silvergate was doomed — the secretly-imposed crypto deposit limit. “The Fed changed their policy based on OCP 2.0, but they don’t want to admit that,” a source told me. “So they looked around and tried to find wrongdoing. The settlement is a big number — but they didn’t find anything.” It makes sense: if the Fed could extract a settlement from a defunct bank, they could point to it as evidence the bank failed through mismanagement, rather than due to regulation-by-bullying.

Another source told me, of the settlements: “For people in Congress, the fact that Silvergate got fined ‘proves wrongdoing’ and vindicates their anti-crypto stance. They wanted to be able to show people they had gotten justice for FTX.”

The settlement with the California Department of Financial Protection and Innovation is almost identical to the Fed complaint, citing “deficiencies with respect to Silvergate’s monitoring of internal transactions.” Initially, sources told me, California wanted a $200 million fine, even though they couldn’t prove negligence or any wrongdoing beyond “deficiencies.” The governor’s office was directly involved, and the first set of proposed charges included “elder abuse” and “elder fraud” — despite the fact that Silvergate had no retail customers.

In all the settlements Silvergate ultimately assented to, there was no accusation of a criminal violation nor any claim that Silvergate had knowingly facilitated money laundering.

One particularly bizarre subplot in this entire affair is the intersection of short seller Marc Cohodes and Senator Elizabeth Warren. As we now know, Senator Warren wrote a letter in December 2022 to Silvergate accusing the bank of breaking the law. From the letter (superscript removed):

The arrangement between FTX and Alameda, which depended on your bank’s depository services, is just one example of the “lax record-keeping and poor centralized controls at the heart of the [FTX] empire’s unraveling” – and may have been illegal. Alameda’s depository account with your bank appears to be at the center of the improper transmission of FTX customer funds. Silvergate’s failure to take adequate notice of this scheme suggests that it may have failed to implement or maintain an effective anti-money laundering program, as required under the Bank Secrecy Act (BSA). What’s more, your bank’s failure to report these suspicious transactions to the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) may constitute yet another violation of the law.

On January 30, 2023, Warren wrote a second letter, complaining about Silvergate’s responses to her first one, this time appearing to pressure the Federal Home Loan Banks (FHLB), which Silvergate was using for last-resort liquidity. It seems her objective was to get the FHLB to pull the rug on Silvergate, forcing them to close. The FHLB eventually declined to renew their monthly facility with Silvergate, which may have been the straw that broke the camel’s back.

“Someone was putting pressure on the FHLB,” one person familiar with the situation told me. “If Silvergate had been allowed to hold to maturity the government-backed securities, they would have been able to stem their losses. They were trying to liquidate them slowly to minimize losses. But the FHLB started getting pressure, so they pressured them to pay back the loans.” To me, it certainly appears like the FHLB responded to Warren’s pressure campaign and cut Silvergate loose. (At the time, FHLB claimed it “did not request or compel” the bank “to prepay its outstanding advances.”)

At the same time, Cohodes was also waging a public campaign against Silvergate, writing numerous memos and tweets, and making video appearances containing all sorts of allegations about the bank.

Cohodes went far further than simply claiming Silvergate (and Signature, his next target) would collapse. He had a habit of calling the two banks “publicly traded crime scenes.” “You have terrorists, you have drug dealers, you have human traffickers,” he said in one interview, referring to SEN. In another interview with The Block, Cohodes repeated the “publicly traded crime scene” aphorism and argued that Silvergate CEO “Alan Lane belongs in prison.”

These extraordinary claims, of course, have never been proven. Silvergate has not faced any criminal liability for either FTX/ Alameda (the DoJ came up empty after its highly touted investigation), nor has any liability regarding human trafficking or terrorism since materialized. Obviously this could change, but as of yet nothing has validated Cohodes’ most extreme claims.

We also know that Cohodes reached out to Warren’s office directly. In January 2023, he emailed her staffer a link to a DoJ complaint (which does not mention Silvergate). “Have you seen this?” he wrote. “Would not be all that surprising if money from ISIS moved through Silvergate, and that would be attention getting.”

Sources with firsthand knowledge told me that Cohodes emailed a slide deck entitled “Silvergate-101” with his allegations against the bank to various members of Congress around the same time. The deck, which I have reviewed, cites anonymous Twitter accounts like @bitfinexed, an account known primarily for spreading conspiracies about the stablecoin Tether.

One individual told me about the Warren-Cohodes relationship: “For sure Warren’s letters intensified the run [on Silvergate]. What makes me sick is that Cohodes put together a deck and was shopping it to members of Congress including Warren. Much of his information was crowdsourced from Twitter.” Regarding Cohodes’ claims that Silvergate had done business with terrorists or human traffickers, the individual told me “there’s no basis for that whatsoever.”

Cohodes doesn’t appear to be particularly shy about his role in Warren’s December 2022 letter. “Who do you think inspired that letter?” he wrote in a quote tweet of the letter in June 2024. Whether or not he actually spoke with Warren’s office, he appears happy to take credit for her work harassing the bank. Cohodes is also a Warren supporter, having told the New York Times during her 2020 presidential run, “She would be great, I think she would be a breath of fresh air.”

Cohodes certainly has a habit of trying to enlist regulators in his short selling campaigns. In January 2023, he sent the Federal Reserve a memo with accusations against Silvergate, and one to the OCC in March 2023 regarding Signature. He also admits to having sent memos to the SEC and FDIC. Many of these celebrity short sellers try to make their predictions into self-fulfilling prophecies by looking for allies in their campaigns; Cohodes appears to have played the game very well.

We don’t know if Warren reciprocated Cohodes’ entreaties. But we do know that she either wittingly or unwittingly helped short sellers by launching a campaign against Silvergate with two blistering letters in which she effectively accused them of aiding and abetting FTX’s crimes. Arguably, she also precipitated the ultimate collapse of Silvergate by pressuring the FHLB to cut off its line of credit, which was the thrust of her second letter. Her standing as member of the Senate Banking Committee gave her words huge weight. If she actually did coordinate with Cohodes to destroy a bank — causing losses to shareholders and creditors, and orphaning depositors — it would be extremely troubling.

After Silvergate filed for voluntary liquidation, Senator Warren pounded her chest, tweeting, “As the bank of choice for crypto, Silvergate Bank’s failure is disappointing, but predictable. I warned of Silvergate’s risky, if not illegal, activity — and identified severe due diligence failures. Now, customers must be made whole & regulators should step up against crypto risk.” Far from being “disappointed” by Silvergate’s failure, she seemed practically thrilled by it. To her, the bank’s failure was evidence that crypto was an unacceptable risk to the banking sector, and so should be ringfenced from the financial system. Of course, she wasn’t a mere impartial observer — her own allegations against Silvergate helped create the atmosphere of concern around the bank that led to the run, especially her claims that they were engaged in illegal activity. It’s easy to take credit for predicting a bank’s collapse when you may be, in fact, one of the reasons the collapse occurred.

This isn’t the first time a Senator has been accused of fomenting a bank run. In June 2008, Senator Chuck Schumer wrote a letter to federal regulators expressing concerns over IndyMac, which likely hastened that bank’s collapse. Consequently, he faced a serious backlash for his role in the failure. But Warren hasn’t been dealt any such recriminations. A Senator can question the solvency of a bank, but it’s self-evident such statements risk becoming self-fulfilling prophecies, especially when made so bombastically, as Warren did.

The collateral damage wrought by the Silvergate wind down was catastrophic. The immediate effect was the destruction of shareholder capital in the business. Additionally, depositors were left scrambling to find new banking partners. The loss of SEN also hurt stablecoin liquidity and likely intensified the liquidity issues faced by USDC as it temporarily de-pegged during the SVB crisis. More damagingly, Silvergate’s collapse was the first trigger in a grave banking crisis that would ultimately take down SVB, Signature, and First Republic, banks which had $538 billion in deposits at the time of the collapse.

Would these banks have collapsed, anyway? It’s possible, but the fact remains: Silvergate was the first bank to suffer a run in that volatile spring of 2023. Banking panics are contagious. It’s not far-fetched to imagine that Warren’s fear mongering caused more than a few depositors to pull their funds from Silvergate. Whether or not she actually colluded with Cohodes — and the public deserves to know the extent of their relationship — a powerful Senator effectively encouraging a bank run which escalated into a serious banking crisis is a complete betrayal of duty.

Sticking up for a bank that did business with FTX, suffered a bank run, was voluntarily liquidated by management, then settled with three different regulators is not an enviable task. But an injustice visited upon a flawed subject is no less of an injustice. Silvergate could perhaps have tightened up its money laundering controls or detected SBF’s improper transfers earlier. But that doesn’t mean it deserved to be harrassed out of existence. One Silvergate insider told me: “We were a group of people that were trying to do the right thing and we understood risk management. It really was a pretty conservative place. And that stems from Alan Lane, and his 40 years of banking expertise.”

Even when I was initially investigating Silvergate and Signature, a number of bankers, sympathetic to my cause, told me it wasn’t worth publicly supporting Silvergate, muttering ominously that the bank may have indeed done some reprehensible things. But this ended up not to be the case. Silvergate was the victim of a scathing and unconstitutional regulatory crackdown — an imperfect victim, but a victim nonetheless. What’s more, Washington’s desire to take down the crypto banks — which they accomplished deftly in March 2023 — was the spark that lit the fire of a massive regional banking crisis, which spread far beyond crypto. Yet today, no one levels criticism at President Biden, Senator Warren, or the Fed for starting a banking crisis in their attempts to stymie the crypto sector.

At the end of the day, if policymakers in Washington want to ringfence the crypto industry and withhold its access to traditional banking, there’s a valid way to do that: through public debate and legislation. If they had passed a law through Congress limiting crypto firms’ access to banks, it would have been devastating to the sector, but it would have at least been valid under the rules of our democracy. But that’s not how the Biden administration officials went about doing things. They effectuated their crackdown through covert backroom dealings, by deputizing the bank sector, and using threats and intimidation rather than public rulemaking. Some portion of the crackdown was disseminated through various agency statements, but much of it was simply handed down verbally with no paper trail, like the presumed 15 percent cap on crypto-related deposits. Other measures were simply taken in the ordinary course of business, such as the refusal to sell on any of Signature’s crypto business.

Ultimately, it’s precisely these marginal cases — the ones that no one wants to stick up for — where we have to draw the line. What happened to Silvergate was a travesty, and the public deserves to know the truth. Sympathetic members of Congress should hold a hearing and give executives at affected banks the chance to testify, with a waiver on criminal liability for sharing confidential supervisory information.

¹ The SEC fines did not involve the transfer of value, as Silvergate was able to ‘apply’ credit for the fines already paid.

² The GAO’s post-mortem on Silvergate blamed rising rates alongside idiosyncratic crypto risks and flighty depositors for the Silvergate collapse. They did not mention regulatory changes which adversely affected the bank’s business model.

³ Note that criminal liability for sharing CSI can be waived if, for instance, the House or Senate calls a hearing on the topic of the banking crisis and offers immunity to individuals invited to testify.

⁴ It’s also worth noting Silvergate purchased the Diem (stablecoin) IP from Facebook based on recommendations made by Biden’s Presidents Working Group, seemingly giving the green light to bank-issued stablecoins. This stance shifted dramatically in 2023 as the Fed ended up effectively banning banks from engaging with stablecoins. This caused the Diem assets to become effectively worthless.

![]()