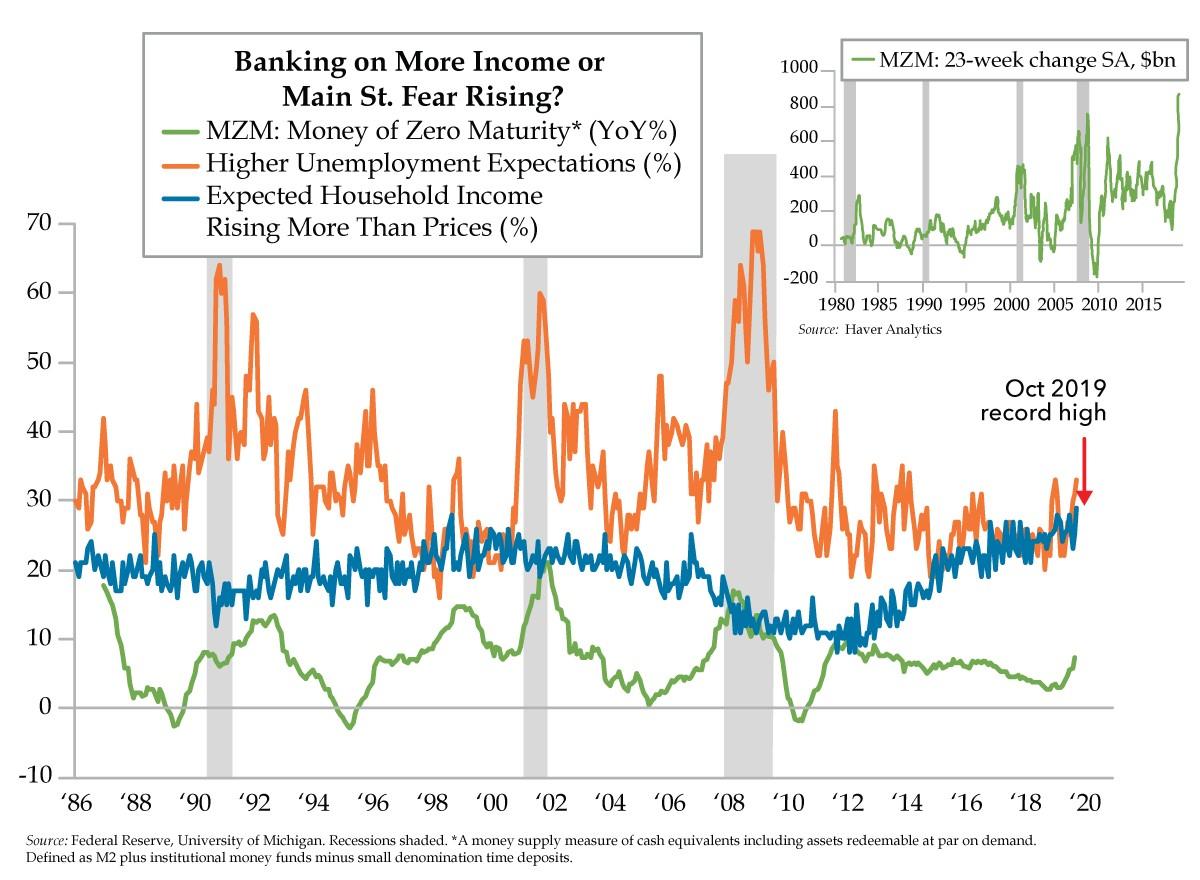

- Uncertainty incites a dash to cash, which we’ve seen at an accelerated pace beginning about five months ago, amounting to $887.4B; In the two weeks ended September 30th, MZM rose by $158.1B, a figure that has only been eclipsed in the immediate aftermath of 9/11

- Declining inflation expectations have netted record levels of households expecting rising real income gains; and yet, consumers are less confident about economic growth with a third anticipating rising unemployment captured in the continued rise in the fear of the unknown

- Those aged 45 and under expect annual income gains of more than twice households as a whole; this corroborates the top-third of income earners’ (managers’) higher unemployment rate expectations vis-à-vis middle-income-earners’ (worker bees’) job market outlook

We Americans are drawn to nicknames that evoke our cities’ characteristics: The Big Apple, The Windy City, Hotlanta. But those passionate Italians demand their cities to be identified by the vividness of color, an element that played right into the logo design of the world’s most iconic sports car. As for the horse, that image was painted on the SPAD S.XIII flew by Francesco Baracca, Italy’s World War I flying ace who recorded an astounding 34 kills before being killed himself in 1918. As recounted by Enzo Ferrari, fate stepped in as such, “In ‘23, I met count Enrico Baracca, the hero’s father, and then his mother, countess Paulina, who said to me one day, ‘Ferrari, put my son’s prancing horse on your cars. It will bring you good luck’. The horse was and still is, black, and I added the canary yellow background which is the color of Modena.”

With this special Daily Feather opening on this Columbus Day that celebrates another famous Italian, we must say it was more the speed of Ferraris that drew us to the theme. As you can see in the spike in the smaller inset chart, MZM, for the money supply, it has galloped away of late. In the last 23 weeks, the surge has been almost entirely accounted for by: Savings deposits at commercial banks ($336.0bn), Institutional money funds ($270.0bn), Retail money funds ($111.3bn), and Demand deposits ($74.6bn).

Add it all up and the last 23 weeks add up to $887.4 billion. We would add that the race into cash has picked up speed. The $158.1 billion, two-week surge ended September 30 was only eclipsed in the immediate aftermath of 9/11.

So why is MZM para-scaling a wall of worry? If you’ll forgive the deeply dissatisfying honesty, we can’t say for sure. There are simply too many divergent messages coming from households. We refer to the preliminary October reading of the University of Michigan (UMich) Consumer Sentiment report.

Here’s one side of the story being told. Quickly declining inflation expectations in the year ahead have collided with consumers anticipating larger income gains. The result: the proportion of those who expect net real (read: inflation-adjusted) income gains was the highest since this question was first posed in the UMich in 1974 (blue line above).

And here’s where things get confusing, with the relaying of the other side of the story. Expecting good tidings inside their own checking accounts did less than nothing when it comes to the prospects for the overall economy. Growth is still expected to slow alongside a rising unemployment rate, at least according to a third of those queried, (orange line above) which is plenty higher than the 20% who expect the unemployment rate to fall.

As for all the hoopla surrounding the Chinese “acquiescing” to buying the same agricultural products they did two years ago but desperately need more today, spontaneous negative references to tariffs were cited by 29% in early October, down from 36% last month. (A QI aside, we humbly classify truly good news on the trade war front as canceled tariffs in place, but what do we know?)

And in what can only be seen as a refutation of the story mainstream media would like to paint, the GM strike was negatively mentioned by 5% compared to the 3% who expressed angst about the impeachment inquiry.

As for that unquantifiable, impossible to articulate fear, that of the unknown captured in the UMich data we featured a few Feathers back, it keeps blazing a trail to the 20%-line that was the last hit when the economy was entering a recession. Recall that this fear gauge is a good predictor of credit spreads which have stubbornly refused to follow stocks’ lead by coming in. Credit investors and households are united in their fearing something they can’t put their fingers on.

QI’s Dr. Gates seemed the right fellow to ask about the perplexing disconnect. But even his sound reasoning left us a bit lost, and he makes perfect sense: “A record number of households said they expect incomes will rise more than prices. Critically, these expectations are rooted in what is already happening to their paychecks. At the same time, more households fear they will lose their jobs and are getting defensive by raising cash.”

There is one explanation that squares the circle.

Overall, households expect their incomes to rise by 2.4%, less than half the pace of those under the age of 45, who anticipate annual income gains of 5.1%. We recently wrote of the top-third of income earners expecting a higher unemployment rate vis-à-vis middle-income-earners for seven months running, a 99th percentile event. You might agree that those with the greatest means to hoard cash, as fast as a Ferrari at top speed, are one and the same with the highest income earners. We’d be remiss to omit that they also dictate the unemployment rate.

According to all central banks, one of the main problems they are called to solve is that countries cannot reach their inflation target of (close to but below) 2 percent. Even their religious trust in the long-discredited Phillips curve cannot explain why price inflation is low in many countries despite historically low unemployment rates. Nonetheless, central banks still enjoy immense credibility. It’s common to hear such sentences as “never bet against the Fed,” the “ECB has big bazooka primed”… and all market participants monitor each public meeting to understand what the next policy could be and how they should be positioned when it arrives.

To reach the inflation targets and “stimulate the economy,” central banks regularly meet to devise ever-new stimulus programs and do not despair when, inevitably, the one-off unconventional interventions quickly become the new normal. For example, the world-famous Quantitative Easing (QE) was supposed to be a one-time emergency response to the 2008 crisis, except it has now become one of the many tools of regular monetary policy, and a key component in market demand for financial assets. An undesired but perfectly predictable side effect of QE is that it allows governments to increase their spending without care for the deficit, and still pay negative interest rates in real terms, so no discipline is imposed, except for some empty promise to reduce the deficit sometime in the future, if the opportunity comes. Several Western countries have embarked in QE, some in many consecutive rounds, but there is no mention of a reverse-course, an eventual, opposite Quantitative Tightening (QT). Only the United States has tried QT, and the Fed has even announced that they were on a stable and data-driven process back to normalization, to try to maintain their reputation of scientific management of the monetary aggregates. However, the Fed had to quickly abandon the plan, and its balance sheet remains massively bloated under any historical measure.

It is abundantly clear that markets are doing well only thanks to monetary life support, and the help provided by QE cannot be taken out without provoking a serious crisis across all the whole investable universe. Now the Fed has embarked in a new round of QE, although Powell denied in the most absolute terms that it is QE.

There is today a veritable alphabet soup of monetary policy tools (QE, OMT, TLTRO, APP, ABCP…) and the result is that no asset class is free of distortion, including the key markets of foreign exchange and corporate debt. All these tools are only more of the same: they apply the same means (create new money out of thin air) to reach the same end (artificially decrease the interest rate). Clearly these interventions have the same side effects as a regular, conventional decrease of the interest rate. Chief among these problems is a general hunt for yield in all markets, the setting in motion of boom-bust cycles, and the inability for pension funds to provide savers with a long-term real return to support retirement and future consumption. Far from being problems confined to banks and the ultra-rich, this diverts resources from savers and wealth generators to the politically-connected.

As historically low-interest rates stifle growth and stimulate consumption but not production, it is easy to find throughout Europe and the US low wage growth, low investment for productivity growth, and growing debt burdens on governments, corporations, consumers.

As always, central banks (like their politician friends) try to solve problems by doing more of the same. Both the Fed and the ECB signaled they’re not finished yet: the ECB lowered its target rate again, and announced a new round of bond purchases. Meanwhile, the Fed lowered its target rate again, likely on the road back to zero. The latest trouble is in the repo market , where banks lend to each other overnight. The Fed has a target rate for interest rates in this market, but the rate skyrocketed well above the upper bound. The Fed stepped in and announced an emergency liquidity assistance (in common speak: bailouts) that will last for months, standing ready to provide print money at will. For a central bank that takes pride in announcing its interventions well in advance to prepare the markets, this is an unseen event. They moved much and quickly, signaling that the problem truly is important. The Fed balance sheet is growing again, and now there is one more moral hazard in town: liquidity risk is not a problem anymore, so the liquidity carries trade is much more profitable. Rest assured that if a liquidity crisis will happen despite interventions, nobody will blame the Fed. Possibly, they will claim the Fed had stepped in too lightly and must do much more.

Still, new monetary tools may be tried in the future. All investors are speculating on what the new tools could be, one possibility is that the ECB (and possibly, in the future, the Fed) could follow the lead of the Bank of Japan in creating a new QE to purchase directly stocks and stock ETFs. Few people won’t be shaken by reading a sentence as “The BoJ was ranked as a top ten shareholder in some 40 percent of all listed companies”, but this is precisely the course of the monetary authorities. However, like all monetary interventions, this would prop up all markets into further bubble territory, while the endemic problems of the economy are never addressed.

Now, what does the market think of all this monetary machinery? The central bank targets an inflation rate, so given its immense credibility, the market should assume that the target will hit. Currently, the inflation rate is below targets, but more troublesome (for the Fed) is that the market expects central banks to continue failing: the expected future inflation rate is on average “only” 1.6 percent in the US , 1.1 percent in Europe , 1.2 percent in Japan . It is thus unclear what this continuous intervention in money is good for, other than pumping up markets and kick the can down the road, pretending that since markets are up then the economy must be doing well.

There are even talks about letting inflation run higher than 2 percent. This number had always been set in stone as the highest number allowed, with central banks standing ready to defend us from higher numbers. Eminent figures such as former IMF Chief Economist Olivier Blanchard have suggested raising the inflation target to 4%, if not more. This would double prices (and halve savings) in about 18 years, less than a generation. So much for the Fed’s goal: “price stability”. But this is not yet generally accepted, and the current fashion is to claim that the inflation target is not 2% but “symmetrical 2 percent”: after years of undershooting we should have years of overshooting, so the long-term average will be 2 percent. In effect, the BoJ and then the Fed have pre-emptively announced that they will not fight inflation unless it becomes too high, without defining “too high”. This pushes a normalization even further in the future, as price inflation of 3 percent, 4 percent, 5 percent would be allowed to continue for years, or until it becomes “too high”, but “too high” has not been defined. The ECB is likely to move in the same direction, especially considering the well-known dovishness of the new head Christine Lagarde.

As is clear from the economic analysis since the Scholastics of five centuries ago, this lack of sound money and apparently infinite money printing does nothing but send confusing signals, increase economic and legal uncertainty, and drive up the rates of time preference in a process of de-civilization and increasing present-orientation. The seeds of all crises since ancient times have been planted through distortions of money, and these concerted crusades of all central banks are no different. Fortunately, there are growing popular movements in Europe and in the United States to push towards normalization of money and interest and to restore sound money and free entrepreneurship. This is a process that started with the 2008 crisis when we saw what happens after 40 years of monetary pumping: the long-run has arrived. Source

StevieRay Hansen

Editor, Bankster Crime

MY MISSION IS NOT TO CONVINCE YOU, ONLY TO INFORM YOU…

#chilssextrade #pedophiles #lawlessness #mexican #children #molested #kill #badbusiness

Tagged Under: Economists, US Money Supply, #Fraud #Banks #Money #Corruption #Bankers,#Powerful Politicians, #Businessmen

![]()