These same money changers were associated with others who engaged in shady business practices in the temple courts. Some sold sacrificial animals, overcharging people who did not bring their own. Others were in charge of examining the animals to be sacrificed, and it was a simple matter to declare an animal “unapproved” and force the worshiper to buy another animal—at an inflated price—from the temple vendors. Such goings-on, exploiting the poor and the foreigner, angered the Lord Jesus and was strictly forbidden in the Mosaic Law (Exodus 22:21; Leviticus 19:34).

Bank stocks crushed by negative interest rates, the broader market goes nowhere in 4 years and is down 44% since 1989 despite BOJ’s equity purchases.

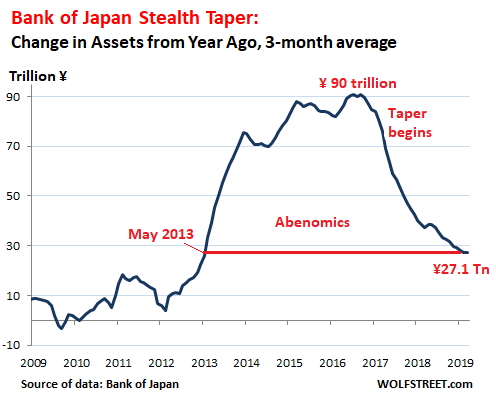

Despite the Bank of Japan’s repeated statements over the years that it would pursue its QE program – or “QQE” as it calls it to distinguish it from the Fed’s flimsy version – with full and relentless force by adding ¥85 trillion ($790 billion) a year to its balance sheet, it hasn’t done that since the beginning of 2017. Instead, it has sharply reduced its QE purchases.

Today, the Bank of Japan disclosed that it had shed ¥2.3 trillion in assets in June, edging its holdings down to ¥565 trillion ($5.2 trillion). There is some volatility in its balance sheet when long-term securities mature. The three-month moving average of its assets, which irons out that volatility, has grown by merely ¥27.1 trillion from a year ago, the smallest 12-month increase since May 2013 – instead of the promised ¥85 trillion. This amounts to an unannounced stealth taper of QE:

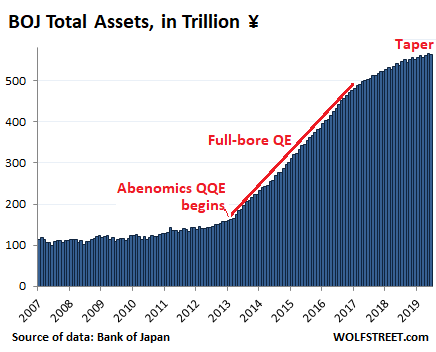

Over the years, the BOJ’s gigantic purchases of Japanese government securities, corporate bonds, equity ETFs, and Japan REITs, have produced an enormous balance sheet. But the rate of increase has now slowed, and the curve at the top is becoming less steep as a result of the stealth taper:

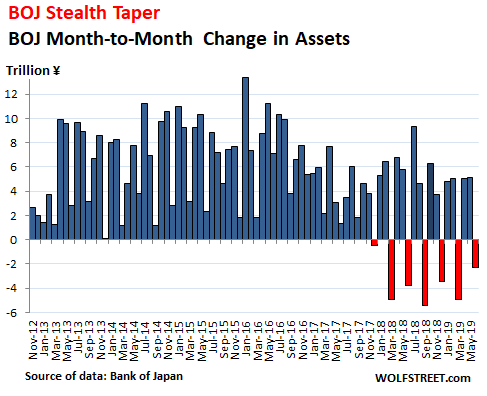

The BOJ’s asset purchases are now low enough to where they no longer cover the amounts of long-term securities that mature and roll off the balance sheet every third month. During these months – June was one of them – the balance sheet shrinks. Then the following two months, it makes up lost ground plus some:

The vast majority of what the BOJ has been buying is Japanese government debt, grabbing essentially every Japanese government bond (JGB) that came on the market. The government would sell new JGBs to its primary dealers that then turn around and sell them for a small profit to the BOJ. In addition, the BOJ bought whatever JGBs came on the market. The BOJ now holds ¥476.3 trillion in government securities — which is the equivalent of about 86% of Japan’s nominal GDP in yen.

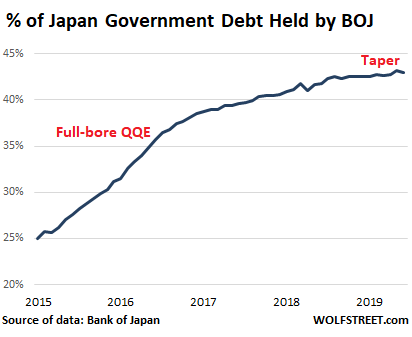

This whole game is of mind-boggling magnitude. But it’s not a game. The debt of the Japanese government has ballooned to ¥1.1 quadrillion or about 200% of nominal GDP (in yen). And the BOJ now owns 43% of this debt, up from 25% in January 2015. But here too, you can see the impact of the taper, as the percentage has essentially been flat since August last year:

In addition, other official institutions, such as the Government Pension and Investment Fund, also own large piles of Japan’s government debt. This concentrated ownership gives officialdom in Japan total control over the government bond market, and yields do whatever the BOJ decides they should do – which currently means that the government issues bonds that have slightly negative yields all the way past 10-year maturities.

So government borrowing is more than free, and that those who still hold this debt pay an asset tax in the form of a negative yield, instead of making a return, and that banks, pension funds, and other institutions that hold assets and need to make money off those assets to stay relevant and meet their obligations have to venture into risky affairs to make a tiny little bit of yield, such as US-originated highly-rated Collateralized Loan Obligations, backed by leveraged loans issued by junk-rated US corporations – and those are currently hot in Japan.

Japanese bank stocks have gotten crushed: the TOPIX Bank Index has dropped 41% from July 2015. The broader Japanese stock market – despite the BOJ’s purchases of equity ETFs – has gone nowhere over this period, with The Nikkei 225 Index up just 5% from July 2015, and still down 44% from its peak in 1989. Source

StevieRay Hansen

Editor, Bankster Crime

![]()